What is Neuroplasticity?

by Lisa Kreber, Ph.D. CBIS

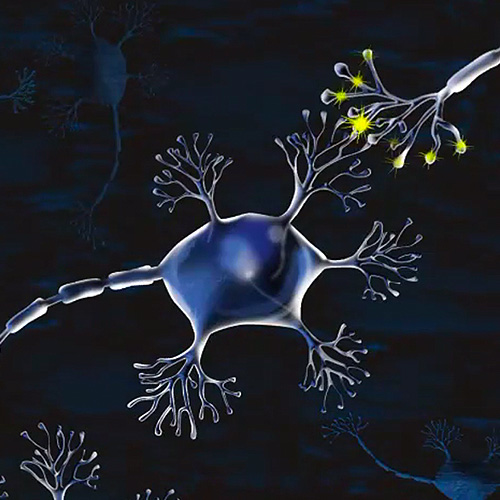

Neuroplasticity has been described as, "The science of how the brain changes its structure and function in response to input." With that, there are two important aspects of this definition. First, the brain really can change in relation to structure and function, unlike virtually any other organ of the body, such as the heart or liver. Specifically, it is designed to grow new structures and create new pathways in the presence of damage or an environmental challenge. Second, the phrase "in response to input," speaks directly to the fact that the brain doesn't really change unless you challenge it. Any task that is familiar, automatic or easy does not challenge your brain, but activities that are difficult and challenging for your brain elicit changes in the neural network.

Neuroplasticity has been described as, "The science of how the brain changes its structure and function in response to input." With that, there are two important aspects of this definition. First, the brain really can change in relation to structure and function, unlike virtually any other organ of the body, such as the heart or liver. Specifically, it is designed to grow new structures and create new pathways in the presence of damage or an environmental challenge. Second, the phrase "in response to input," speaks directly to the fact that the brain doesn't really change unless you challenge it. Any task that is familiar, automatic or easy does not challenge your brain, but activities that are difficult and challenging for your brain elicit changes in the neural network.

Dr. Donald Hebb, a Canadian neuropsychologist, famously stated, "Neurons that fire together, wire together." This means that neurons that communicate with each other end up being part of the same neural network and want to continue to communicate with each other. Repetition can be important in affecting this process.

It is important to point out that neuroplasticity or simply, "plasticity" is not an occasional state in the nervous system, it is a normally ongoing state.. This is because the brain in is designed to change in response to changes in the environment and not just through injury recovery. As neurologist Dr. David Perlmutter noted, " Neuroplasticity provides us with a brain that can adapt not only to changes inflicted by damage, but allows adaptation to any and all experiences and changes we may encounter." These changes occur in the anatomy through input to the neural system, as well as through output. In the treatment environment, this input occurs along afferent connections (from the periphery to the central nervous system), for example, with challenges to the brain through rehabilitation activities and learning a new skill. In turn, outputs from the brain to efferent targets (from the brain to the periphery) are manifested in ways that help us, as clinicians, measure progress, e.g., how fast and accurately is a patient able to do a task?